Illustration of cogs whirring in someone's head

In my first story ‘User Experience is …’ I promised that …

"over the course of a few stories, I’ll try and cover a few of the sciences we draw upon in our art as a creative community to create engaging experiences."

And in my last story I talked around how User Experience is User Research. My previous article I started the conversation on how User Experience is … Psychology. This time we venture further into the Psychology field and focus more on Behavioural Economics.

Illustration of cogs whirring in someone's head

Behavioural economics combines insights from psychology, judgment, and decision making, and economics to generate a more accurate understanding of human behaviour.

Economics has long differed from other disciplines in its belief that most if not all human behaviour can be easily explained by relying on the assumption that our preferences are well-defined, stable across time and are rational.

Richard Thaler a Nobel winning economist from upstate New York inspired the creation of behavioural science teams, often calling them “nudge units” in public and private organisations around the globe. Together with Cass Sunstein, he wrote a book in 2008 called Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, which suggests that there are many opportunities to “nudge” people’s behaviour by making subtle changes to the context in which they make decisions.

Think about the last time you purchased a customisable product. Perhaps it was a laptop computer. You may have decided to simplify your decision making by opting for a popular brand or the one you already owned in the past. You may then have visited the manufacturer’s website to place your order. But the decision making process did not stop there, as you now had to customise your model by choosing from different product attributes (processing speed, hard drive capacity, screen size, etc.) and you were still uncertain which features you really needed. At this stage, most technology manufacturers will show a base model with options that can be changed according to the buyer’s preferences. The way in which these product choices are presented to buyers will influence the final purchases made and illustrates a number of concepts from behavioural economic (BE) theories.

Illustration of a person, showing different paths, different directions and different approaches

This theory assumes that humans have stable preferences and engage in maximised behaviours. In an ideal world, defaults, frames, and price anchors would not have any bearing on consumer choices. Our decisions would be the result of a careful weighing of costs and benefits and informed by existing preferences. We would always make optimal decisions.

This is in direct competition with rational choice and shows that decisions are not always optimal. Our willingness to take risks is influenced by the way in which choices are framed, i.e. it is context-dependent.

Tversky and Kahneman’s work shows that responses are different if choices are framed as a gain or a loss. This happens because we dislike losses more than we like an equivalent gain: Giving something up is more painful than the pleasure we derive from receiving it.

The overarching notion behind this theory is that people think of value in relative rather than absolute terms. For example, they derive pleasure not just from an object’s value, but also the quality of the deal, its transaction utility. In addition, humans often fail to consider fully opportunity costs (tradeoffs) and are susceptible to the sunk cost fallacy.

A core idea behind mental accounting is that people treat money differently, depending on factors such as the money’s origin and intended use, rather than thinking of it in terms of formal accounting.

The principle of limited knowledge or information point to experience, good information, and prompt feedback as key factors that enable people to make good decisions.

Political, environmental or health change can often be invisible, diffused, and a long-term process. Pro-environmental behavioural by an individual, such as reducing carbon emissions, does not lead to a noticeable change. The impact of smoking, is at best noticeable over the course of years, while its effect on cells and internal organs is usually not evident to the individual.

These are choices that are made due to limits in our thinking processes, especially those we make as consumers. Often related to pricing and value perception, this also includes anchoring, a process whereby a numeric value provides a non-conscious reference point that influences subsequent value perceptions.

Both limited information and ‘irrational’ decision making suggest that human decisions are strongly influenced by context, including the way in which choices are presented to us. Behaviour varies across time and space, and it is subject to cognitive biases, emotions, and social influences. Decisions are the result of less deliberative, linear, and controlled processes than we would like to believe.

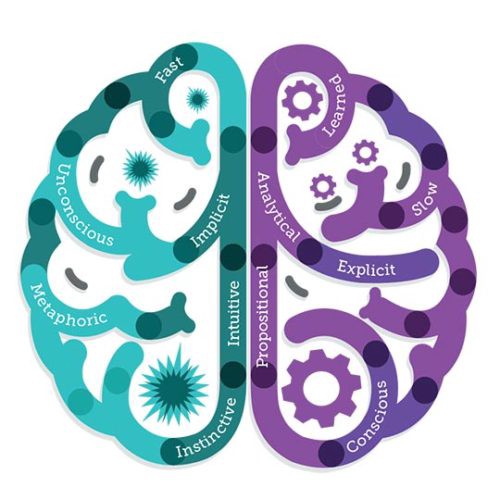

Availability serves as a mental shortcut if the possibility of an event occurring is perceived as higher simply because an example comes to mind easily. For instance, a person may deem pension investments too risky as a result of remembering a family member who lost most of her retirement savings in the recent recession. Another example is the feelings, good or bad that surface automatically when we think about an object.

Diagram showing how the brain processes information

Availability and affect are processes internal to the individual that may lead to bias. The external equivalent of these processes is salience, whereby information stands out, because it is novel, or seems relevant, which is more likely to affect our thinking and actions.

In order to achieve the status quo, habits are needed to be formed, which are automatic behavioural patterns that are the result of repetition and associative learning. Status quo bias looks at the preference for things to remain the same, such as a tendency not to change behaviour unless the incentive to do so is strong.

This looks at how present events are weighted more heavily than future ones; for example, many people would prefer to receive £100 now over £110 in a month’s time.

Diversification bias occurs when we fail to predict accurately our future preferences. For example when shopping I may choose a variety pack of cereal, because I’m unable to understand what I might want in the future. I then might realise after finishing the cereal I would have enjoyed my breakfasts more if I had just stuck to my favourite kind. In the case of food, diversification bias could be particularly strong if you make your purchasing decision right after a meal.

When we make plans for the future, we are often too optimistic. We can be subject to planning fallacy by underestimating how long it will take us to complete a task and ignoring past experience. Similarly, when we try to predict how we will feel in the future, we may overestimate the intensity of our emotions.

The level of happiness that I expect to feel during my next holiday, for example, is likely to be higher than how I will rate it during the actual experience. There are different explanations for this error, including how we remember past events. The memory of a past holiday is likely to be non-representative of the holiday overall and I may evaluate my last holiday based on the most pleasurable points and its end, for example, rather than the average of every moment of the experience.

Fairness is related to a human desire for reciprocity, our tendency to return another’s action with another equivalent action. Reciprocity, however, can have positive and negative aspects. As Ernst Fehr’s work in this area has shown, people’s responses to positive actions are often kinder than a self-interest model would predict, but on the flip side it can also lead to more sever responses to negative actions.

So if I’ve piqued you’re interest with these examples and you want to get involved with another subject of study, why not look into behavioural economics and use it for good (not evil) in your designs! Next up in the series I’ll be looking into how User Experience is … designing with insight.

Originally written as part of the ‘User Experience is …’ series for UX Collective.